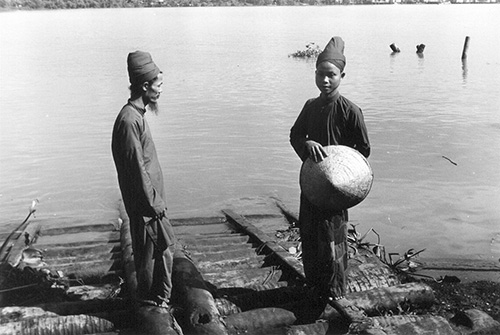

Balaban near My Tho in 1971

In 1971–1972, on a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, I returned to Vietnam with a tape recorder to collect the oral, sung poetry know as ca dao. I was twenty-seven and two years earlier had served in Vietnam as a conscientious objector and been wounded. Now the war still raged in the countryside. Indeed, in some of the recordings featured here, mortar and rifle fire can be heard in the background. As Vietnam was being torn apart and the cities were filling with farmers driven from the countryside, I imagined that I might save evidence of a poetic culture that could soon disappear.

I recorded thirty-five singers, men and women and children. The youngest was a boy of five; the oldest, a woman nearing eighty. In occupation, they included farmers from the Mekong Delta and an aging mandarin from the last imperial court in Huế, but also school children, river peddlers, and a woman who collected herbs in the forest and sold them from her stilt house by the river. From such singers I gathered love laments, songs about birds and beasts, poems of social protest and social order (usually renegotiating Confucian obligations), patriotic poems, lullabies, courting songs with male and female replies, and children’s game songs. Most of the poems had never been written down before in Vietnamese, much less recorded and translated into a foreign language.

Ca dao are always sung to melodies without instrumental accompaniment by individuals singing in the first person; ca dao are lyrical rather than the narrative in form. The singers, to quote Confucius, merely “give vent to their complaint.” Usually the poems are quite brief. Lyrics complete in one couplet are common, creating a fourteen-syllable construct shorter even than the Japanese haiku. But the form also invites an intricate stringing together of couplets linked by internal rhyme, as it was in Vietnam’s greatest written poem: the 3,250 lines of Nguyễn Du’s classic, Truyện Kiều (The Tale of Kieu) of 1813.

Today the ca dao tradition continues, as it has for more than a thousand years.

—John Balaban

The Sàigòn River

The Sàigòn River slides past the Old Market,

its broad waters thick with silt. There

the rice shoots gather a fragrance,

the fragrance of my country home,

recalling my motherhome, stirring deep love.

Sông Sàigòn chảy dài Chợ Cũ,

Nước mênh mông nước đổ phù sa.

Ngọt ngào ngọn lúa bát ngát hương (thơm)

Hương lúa của quê nhà (hò hò);

Hướng về quê mẹ đậm đà tình thương.